Worship Service Sundays at 10am | In-Person or Livestream Here

Holy Week Schedule: 4.13 Palm Sunday Service at 10am

4.18 Death Cafe at 5pm & Good Friday Service at 7pm

4.20 Easter Sunrise Service at 7am & Easter Worship Service at 10am

Sermon 09.22.2024: The Author of Our Lives

The story of Joseph and his brothers includes generational trauma, dysfunction, and the grace of God. How do we tell our own family stories? Can we claim the good, bad, and ugly of what happens and see a path through it toward God?

Scripture

Genesis 37:3-8, 17b-22, 26-34; 50:15-21

Now Israel loved Joseph more than any other of his children, because he was the son of his old age; and he had made him a long robe with sleeves. But when his brothers saw that their father loved him more than all his brothers, they hated him, and could not speak peaceably to him.

Once Joseph had a dream, and when he told it to his brothers, they hated him even more. He said to them, “Listen to this dream that I dreamed. There we were, binding sheaves in the field. Suddenly my sheaf rose and stood upright; then your sheaves gathered around it, and bowed down to my sheaf.” His brothers said to him, “Are you indeed to reign over us? Are you indeed to have dominion over us?” So they hated him even more because of his dreams and his words.

The man said, “They have gone away, for I heard them say, ‘Let us go to Dothan.’” So Joseph went after his brothers, and found them at Dothan. They saw him from a distance, and before he came near to them, they conspired to kill him. They said to one another, “Here comes this dreamer. Come now, let us kill him and throw him into one of the pits; then we shall say that a wild animal has devoured him, and we shall see what will become of his dreams.” But when Reuben heard it, he delivered him out of their hands, saying, “Let us not take his life.” Reuben said to them, “Shed no blood; throw him into this pit here in the wilderness, but lay no hand on him” —that he might rescue him out of their hand and restore him to his father. Then Judah said to his brothers, “What profit is it if we kill our brother and conceal his blood? Come, let us sell him to the Ishmaelites, and not lay our hands on him, for he is our brother, our own flesh.” And his brothers agreed. When some Midianite traders passed by, they drew Joseph up, lifting him out of the pit, and sold him to the Ishmaelites for twenty pieces of silver. And they took Joseph to Egypt. When Reuben returned to the pit and saw that Joseph was not in the pit, he tore his clothes. He returned to his brothers, and said, “The boy is gone; and I, where can I turn?”

Then they took Joseph’s robe, slaughtered a goat, and dipped the robe in the blood. They had the long robe with sleeves taken to their father, and they said, “This we have found; see now whether it is your son’s robe or not.” He recognized it, and said, “It is my son’s robe! A wild animal has devoured him; Joseph is without doubt torn to pieces.” Then Jacob tore his garments, and put sackcloth on his loins, and mourned for his son many days.

Realizing that their father was dead, Joseph’s brothers said, “What if Joseph still bears a grudge against us and pays us back in full for all the wrong that we did to him?” So they approached Joseph, saying, “Your father gave this instruction before he died, ‘Say to Joseph: I beg you, forgive the crime of your brothers and the wrong they did in harming you.’ Now therefore please forgive the crime of the servants of the God of your father.” Joseph wept when they spoke to him. Then his brothers also wept, fell down before him, and said, “We are here as your slaves.” But Joseph said to them, “Do not be afraid! Am I in the place of God? Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good, in order to preserve a numerous people, as he is doing today. So have no fear; I myself will provide for you and your little ones.” In this way he reassured them, speaking kindly to them.

Sermon

I love the story of Joseph. It has it all. Drama. Poor parenting choices. Rags to riches. Hero’s journey. It also takes up a large section of the Book of Genesis. As Biblical scholar Collin Cornell writes: “At 14 chapters, it is the longest continuous narrative in Genesis, occupying roughly a quarter of the whole book. It traces a complex arc: a movement from adolescence to maturity, hubris to responsibility, and fraternal rivalry to reconciliation.”[1]

Joseph is Jacob’s second youngest son, and the first-born son of Jacob’s favorite wife, making him Jacob’s favorite son. Joseph is also a dreamer. And his dreams get him in trouble, because he dreams that his older brothers will bow down and honor him. So, what happens to the favorite, snotty younger brother when Jacob sends him to “see about the shalom your brothers?” (37:14)

First, they want to kill him, naturally. They are brothers, after all. But then one of the brothers considers that a bit of an overreaction and they decide to leave him in a pit to die on his own. And remember—people look to scripture to support “family values.”

Eventually, they sell him to traders, dip his coat in goat’s blood and take it home to dad and say, “Gee, dad, we don’t know what happened to your favorite child?” Filial love at its finest.

Remember that in the book of Genesis, the idea of killing their brother is a callback to the beginning, when Cain kills his brother Abel. By not re-playing out the Cain and Abel murder story, the brothers are able to live out a new ending to the conflict, no matter how deplorable their behavior still is.

Joseph ends up working for the pharaoh of Egypt—it’s a great story. If you haven’t read it, I invite you to spend some time with it this week. In the intervening years, a famine comes upon the land. Because of Joseph’s dreams and visions, Egypt is well prepared for the famine. The rest of the family of Jacob, not in Egypt, are not.

The brothers end up encountering Joseph when they come to Egypt seeking food, but they don’t recognize him. He recognizes them, however. He puts one of them in prison, which is still better than leaving them in a pit or trafficking them to traders, but tells the others to take grain home to their father and to bring their youngest brother back if they want to save Simeon from prison.

Even though the brothers don’t recognize Joseph, they correctly assume that this development is connected to their earlier actions against Joseph.

They go home and report to Jacob. He rather astutely comments, “I am the one you have bereaved of children. Joseph is no more and Simeon is no more and now you would take Benjamin.”

They run out of grain again, and he tries to send them back. Judah says, “Dad, we already told you. We can’t go back unless we take Benjamin. But I promise I’ll take care of him.”

So Judah begins to live into his role as his brother’s keeper.

Eventually, Jacob dies, and the brothers still worry about Joseph. Here’s the final part of our Scripture passage:

Genesis 50:15-21

Realizing that their father was dead, Joseph’s brothers said, ‘What if Joseph still bears a grudge against us and pays us back in full for all the wrong that we did to him? ’So they approached Joseph, saying, ‘Your father gave this instruction before he died, “Say to Joseph: I beg you, forgive the crime of your brothers and the wrong they did in harming you.” Now therefore please forgive the crime of the servants of the God of your father. ’Joseph wept when they spoke to him. Then his brothers also wept, fell down before him, and said, ‘We are here as your slaves. ’But Joseph said to them, ‘Do not be afraid! Am I in the place of God? Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good, in order to preserve a numerous people, as God is doing today. So have no fear; I myself will provide for you and your little ones. ’In this way he reassured them, speaking kindly to them.

Jacob had sent Joseph to inquire about the shalom, the well-being, of his brothers right before his brothers trafficked him into slavery. And it is only now, after all these years, that Joseph is able to see to the shalom of his family by saving them from the famine.

But what he can’t quite do is rise above his family system. The dysfunction that led brothers to sell their little brother is still in place. The brothers express their “dismay” when they realize Joseph is still alive. That’s their reaction.

If there was joy or celebration, the author doesn’t tell us. Their dismay he noted.

Yet even in a family as dysfunctional as the family of Jacob, God is at work. That is important to remember as you read Joseph.

Some commentators want this to be a story about how great Joseph is. Joseph is a flawed character in a flawed family. This is a text about how God works through people, even people like Joseph. Because if God can work through the imperfect people whose lives are chronicled in Scripture, then God can work through you and me.

And Joseph seems to get that too, finally.

“Do not be distressed”, he tells his brothers, “or angry with yourselves. Even if you sold me here, for God sent me here before you to preserve life. God sent me before you to preserve for you a remnant on earth, and to keep alive for you many survivors. So it was not you who sent me here, but God.”

Joseph, who has good reason to be bitter, is not. He sees blessing in his having been sold into slavery by his own brothers.

More than that, he sees Divine blessing.

I want to be clear about something.

Joseph’s comment is one he can only make for himself. If Joseph came into my office and told me this story, I would never, ever, ever say to him, “Don’t be upset, Joe. I know your brothers were trying to kill you, but God had them sell you into slavery so that you could then save them some day in the future. See, it was good news, part of God’s plan!”

We also don’t claim God’s presence in our lives at the expense of other people’s lives. Some of you may have heard me say last year that our home in Boise was randomly shot at, one of the many terrible gun violence stories in our country. I feel incredibly relieved, lucky, fortunate that my family was not in our home when the shooting happened. We had 14 bullet holes to have repaired and a little trauma to process, but we were okay.

But I would not say that God was looking out for us, or sparing our lives, in particular, when more than 40,000 people in this country die each year because of gun violence, including the 24 injured and 4 dead in Birmingham Alabama last night. We don’t claim God’s providence or care in our lives at the expense of someone else’s life. God’s providence is for all and for creation.

When we look for providence in the particularities of our lives, we look for the ways it connects us to others, not the way it benefits us at the expense of others.

We can help each other frame our stories. We can suggest ways that our friends and loved ones may seek connection to the details of their lives to God’s story. We cannot determine how another person gets to experience God’s working in their lives. When we try to tell someone else what their experience has been, they lose the ability to write their own story.

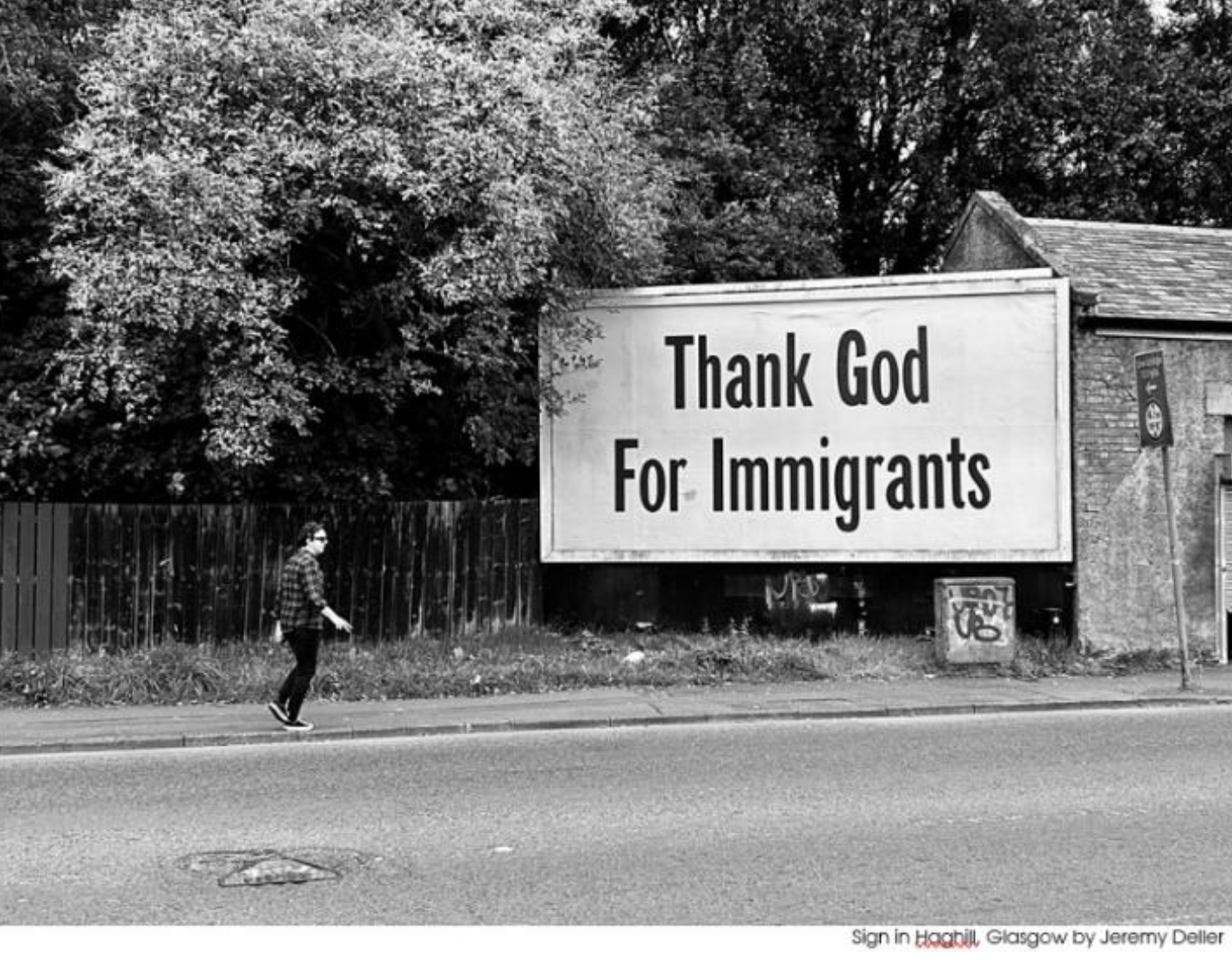

I see that happen in the news when we decide people are protesting “incorrectly” about the injustices faced in our society. To be clear, it is fair to hold different viewpoints.

What’s not fair is to assume someone else’s experience is the same, or should be the same, as yours. When someone says they have experienced sexism or racism or ageism, or whatever flavor of injustice—it is not for us to dismiss or invalidate their experience. It is upon us to listen to their stories, to see the way they experience the journey of their lives. We can share how our experience is different. We can’t presume we know how’d we respond, because their journey is theirs, and ours is ours.

I have a friend who told me that every time her husband leaves the house to go to the store, or go to work, or take their daughter to school, she’s terrified.

This friend is black. I’m not. I confess I don’t know what it is like to have that kind of fear. My husband and sons can navigate the world with a presumption of safety that my friend and her family cannot. So, I listen to her. And I am reminded to check my assumptions when I hear the news reports, and wonder whose perspective we’re hearing, and whose perspective is going unvoiced.

It’s human nature, this tendency to forget that other people have a different perspective than we do. In some ways, it’s the root of the story of Jacob’s family. Jacob loves Rachel, so he doesn’t care how it might seem to his other sons when he favors her son Joseph. Joseph’s perspective is that of the favorite son, who can say anything without retribution. No wonder he doesn’t understand why his brothers would not like his dreams as much as he does.

The rest of the brothers—are they so wounded by being overshadowed by Joseph that they don’t see the love their flawed father has for them?

Joseph was able to look back over the story of his life and trace a path of how God worked through the good, the bad, and the ugly moments of his journey. How do we view the stories of our lives?

And do we feel we have the permission to claim our own version of the story? So often, in my own life, and in what I hear in conversations with friends, we seem to be stuck in the stories other people have told about us.

I had a youth group kid once who was the most creative and talented kid. Her parents had a very clear set of expectations for who she was going to be when she grew up. From what she was going to major in to where she was going to college. Those expectations, the story they taught her to tell herself, was somewhat at odds with her particular gifts. In order for her to tell her own story, she had to disappoint people she loved, and who loved her.

Maybe that was part of Joseph’s journey too. Hearing his father tell the story of his being the favored son and the hero of the story. Hearing his brothers tell the story of his being the bane of their existence and the villain of their story. It took Joseph until the very last chapter of Genesis to tell the story the way he had experienced it.

“Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good, in order to preserve a numerous people, as he is doing today. So have no fear; I myself will provide for you and your little ones.”

As someone who is living into the process of claiming my own part of my birth family story, I suspect that moment for Joseph was a powerful one. To make a claim for himself, for God’s movement in his life, for his hope for the future. What a gift.

There is beauty in looking for blessings, in looking for God’s hand, even in the worst situations.

When our brothers leave us in a pit to die, it is understandable that we could grow bitter and plot revenge against them. But what if that had been Joseph’s entire focus the rest of his life? We see that plenty—people focused so much on the wrongs that have been done to them that they can’t find a way past it.

I want to be more like Joseph, looking for God’s hand in our lives. Not as the cause of the difficulty, but as the agent of redemption of our lives in the midst of the difficulty.

And we don’t look for God’s hand in our lives so we can just pretend that everything is fine. Joseph’s brothers needed to apologize to him. The fact that God was able to work in the situation didn’t erase the fact that Joseph’s family had some “issues” and that slavery and human trafficking is wrong, and a sin, and should be abolished wherever it exists.

As I mentioned at the beginning of worship, the story of God’s working through the dysfunction of the family of Jacob is a good illustration of the concept of providence. Providence comes from the Latin, ‘pro videre’, to fore-see, to fore-ordain.

Providence is not fate. God is not a puppet master or fortune teller. We still have the agency to make decisions and take actions that affect our lives and the lives around us. But providence means that through the good and the bad experiences that happen to us, God is at work, creating new ways for us to see blessing.

Providence is related to the idea of God as creator. The God who created us is still at work, in the midst of everything, creating new life.

The word “life” flows through this Joseph story. “Do not be distressed”, he tells his brothers, “or angry with yourselves. Even if you sold me here, for God sent me here before you to preserve life.”

Providence is best seen when you are looking back on your life.

My earliest memory is of my parents telling me that they prayed to God for a baby, and that God found me for my family. My adoption story was framed by an experience of providence. Long before I could make any decisions about God, God was working for good in my life.

As I’ve been discovering things about my birth family these past few years, I’ve been thinking about providence a lot. What would my life have been had I not been adopted? Literally everything about me would be different. Everything. I would not be standing before you today, with the experiences that have made me into the woman I am.

I wonder if Joseph thought about that. What would his life had been like had his brothers not sold him to traders? Would he have risen to the top in his hometown, as the spoiled, almost youngest son of a patriarch the same way he rose to the top as Pharaoh’s advisor? Would his family have died in the famine, if he wouldn’t have been there to interpret Pharaoh’s dream that allowed Egypt to store up grain for the lean years?

Providence is not about second guessing your life. I’m certainly not second guessing mine. I’m so grateful for having been adopted and for the life I am leading, even as I’m also grateful for everything I’ve learned about my birth family.

All of these “I wonder” moments for me, instead of leading me off down trails that don’t lead anywhere, have actually been leading me to a deep center, a place in myself where I feel grounded and heading toward wholeness, toward shalom.

I hope you’ll be able to join us this afternoon for a screening of the show Jack has a Plan. It is about how we think about end-of-life options, and the story of a man who wanted to write a different ending for his story. It wasn’t without disagreement with his loved ones. Because sometimes we have different ways we want our loved ones stories to go. It is important to think about our wishes for end of life, and to discuss them with our loved ones. This afternoon’s event is a place to start that conversation.

When your life feels like your brothers just sold you to traders, remember that even then you are being held in the palm of God’s hand. Look for your story and write a better ending.

And as you go back out into the world, remember that your kindnesses and good deeds may be the providential hand of God in someone else’s life. Listen for their stories and work for justice so they may write better endings. The heart of the story of the Book of Genesis is about how the characters learn to be each other’s keepers, to look after the shalom—the health and wholeness— of the people around them. That is the creativity inherent in God’s providence.

I’m grateful for the way our stories come together and for the God who helps us be the author of our lives. Amen.

1 https://www.workingpreacher.org/commentaries/narrative-lectionary/god-works-through-joseph/commentary-on-genesis-373-8-17b-22-26-34-5015-21-2

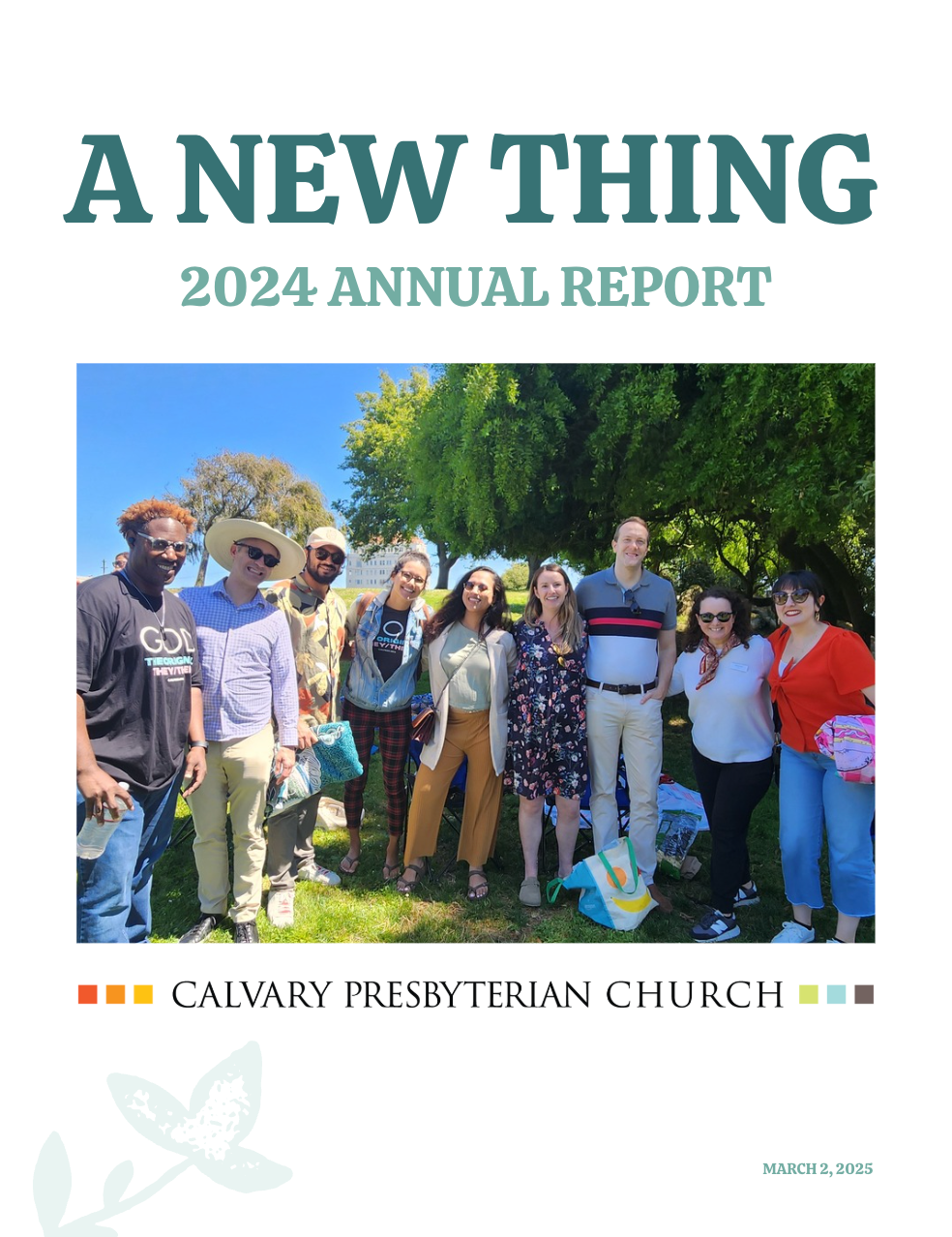

About Us

Our mission is to nurture and inspire our faith community to transform lives for Christ.

Church Office Hours

Sunday:

9:30am - 1pm

Monday - Friday:

10am - 4pm

Saturday: Closed

Contact Info

Calvary Presbyterian Church

2515 Fillmore Street

San Francisco, CA 94115

1 (415) 346-3832

info@calpres.org

Calvary is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

Tax ID # 94-1167431