Sermon 03.09.2025: Lent 1: Half Alive

In today's scripture reading, someone asks Jesus who, exactly, qualifies as a neighbor. Jesus tells the story of a person found half dead on the side of the road, but seen by at least one passerby as half alive, a neighbor worthy of care. Join us as we consider the question for today's world.

Scripture

Luke 10:25-37

The Parable of the Good Samaritan

Just then a lawyer stood up to test Jesus. ‘Teacher,’ he said, ‘what must I do to inherit eternal life?’ He said to him, ‘What is written in the law? What do you read there?’ He answered, ‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbour as yourself.’ And he said to him, ‘You have given the right answer; do this, and you will live.’

But wanting to justify himself, he asked Jesus, ‘And who is my neighbour?’ Jesus replied, ‘A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell into the hands of robbers, who stripped him, beat him, and went away, leaving him half dead. Now by chance a priest was going down that road; and when he saw him, he passed by on the other side.So likewise a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan while travelling came near him; and when he saw him, he was moved with pity. He went to him and bandaged his wounds, having poured oil and wine on them. Then he put him on his own animal, brought him to an inn, and took care of him. The next day he took out two denarii, gave them to the innkeeper, and said, “Take care of him; and when I come back, I will repay you whatever more you spend.” Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbour to the man who fell into the hands of the robbers?’ He said, ‘The one who showed him mercy.’ Jesus said to him, ‘Go and do likewise.’

Sermon

A teacher of the law asks Jesus a question we know he already knows the answer to. Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?

Jesus lets him show off and the man cites not just one book of the Bible but two books. Gold star!

Love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength, and with all your mind, which is from Deuteronomy 6:5.

And Love your neighbor as yourself, which is Leviticus 19:18.

He could have called it good and stopped there, but we’re told he wanted to justify himself, so he asked Jesus, “and who is my neighbor.”

I want to justify myself all the time too, so I get it. My neighbor is the person I get along with, right? The one who agrees with my politics and theology and who wants to build a caring and compassionate world, right?

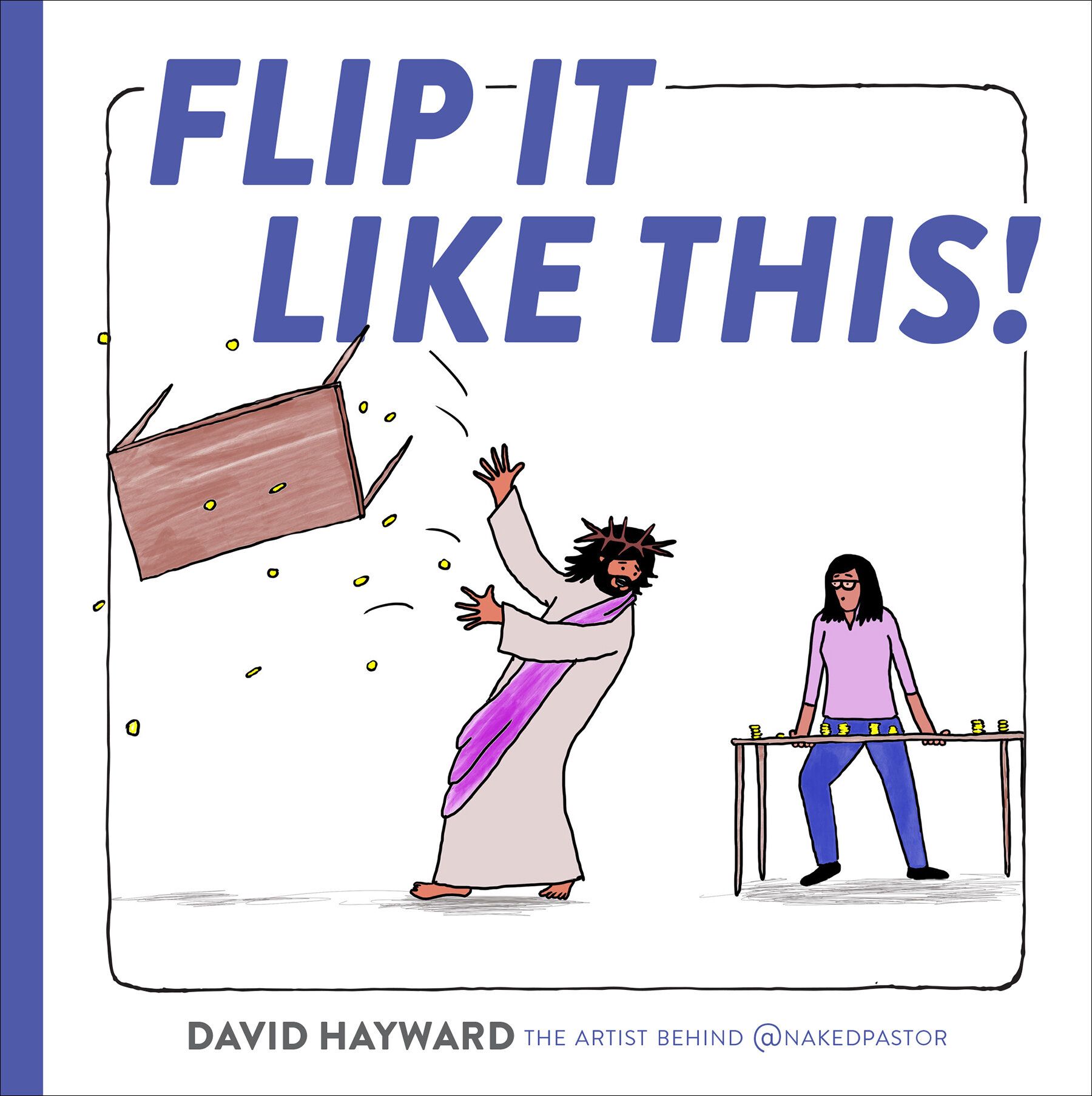

But the people dismantling the government like Godzilla demolishing Tokyo, they aren’t my neighbor, right? I don’t have to love them as I love myself.

Or the people looking up to nazis and siding with authoritarian strong men while alienating our allies—I don’t have to see them as my neighbor, right? I don’t have to love them as I love myself.

The people for whom you would like to justify your lack of neighborly concern may be different than the people on my list. And that’s the point.

We all have a list.

We all want to justify ourselves before Jesus.

Who is our neighbor?

For the writers of Leviticus, quoted by the lawyer trying to test Jesus, your neighbor was the Israelite man who lived next to you and who submitted himself to the Law and the Holiness Codes. You can read through the whole book of Leviticus for a better sense of those codes, although I don’t recommend it. It isn’t light reading.

There were expectations of hospitality and welcome for the stranger, but strangers were not neighbors in Leviticus. And Samaritans were certainly not considered neighbors.

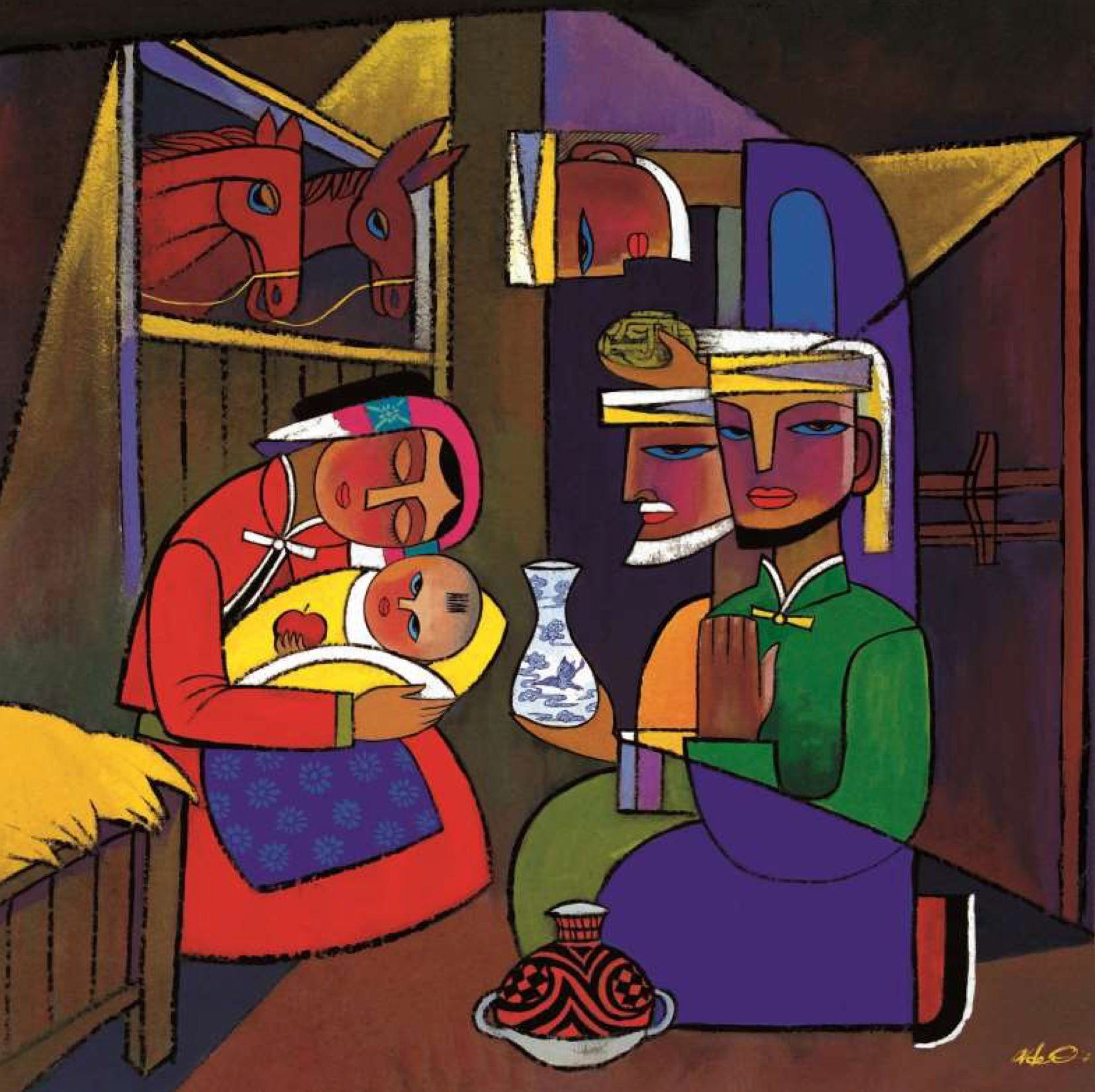

The fight between the Judeans and the Samaritans was a family fight. Samaritans were people descended from the same religious tradition as Israel, family members who went different ways, and whose religious practices were not recognizable to each other as faithful. They were not neighbors. They were estranged family, with the animus that comes with it.

Close your eyes and think of the person you dislike the most, that visceral revulsion that makes you not want to be within 100 miles of that person—the person about whom you’d like to justify yourself to Jesus so you don’t have to care for them—that’s who you should picture in this parable when they mention the Samaritan.

And it would be bad enough to be told that person was lying on the side of the road half dead and you were expected to help them, to be their neighbor.

Now imagine, the half dead person on the side of the road is you, and that person you cannot abide is the one who stops to take care of you.

Jesus expands our definition of neighbor, both in the Parable, and also through his daily living. He eats with sinners, outcasts, and women. He touches lepers and the unclean. Jesus showed us that his Holiness was what was contagious, not our uncleanness.

Jesus calls his followers to see the world in a more expansive way than the writers of Leviticus were able to see it.

And the Levitical writers weren’t bad people. They didn’t set out to create a bunch of rules that make no sense to us, just to punish or exclude people. They were a small tribe of people, trying to maintain identity in a time of exile and dislocation.

When you fear the future and safety of your people in a diverse world, filled with anxiety, we can have compassion for why they wanted to so narrowly define their community.

We see it today, with politicians wanting to deport immigrants and wanting us to fear diversity, equity, and inclusion policies as if unqualified people are coming for our jobs, our security, our way of life.

Some see these policies as racist, maybe even evil, and no matter how you label them, they are dangerous. But underneath what we might label as racism and hatred is fear. These are not the policies of confident and secure people. These are the policies that grow out of our fear.

Fear that there isn’t enough.

Fear that manufacturing jobs are gone and won’t come back.

Fear that our best days are behind us.

Fear that the world doesn’t look to us as a leader.

Fear of people we don’t understand.

Fear of a culture that has changed to welcome people we don’t understand.

Fear because things seem half dead and we aren’t sure if we have what it takes to care for what is half alive.

So, Jesus tells a story for all of us who are afraid. And we’re all afraid of something, whether it is people we’re told to fear or the people who tell us to fear.

Who is my neighbor?

Jesus interprets Leviticus to say that Everyone is our neighbor.

“Who is my neighbor?” is the question the lawyer asks when he quotes Leviticus. But the parable Jesus offers, and this passage quoted from Leviticus, might actually better answer the question “how do I act as a good neighbor?”

And even though I doubt it was the intention of the Levitical writers, Leviticus supports well what Jesus did and how he showed us to live.

Leviticus instructs us to:

Provide for the hungry.

Deal fairly with both the rich and the poor.

Pay a fair wage at the end of each day.

Be honest.

Do not cheat the deaf or the blind.

Seek justice over vengeance.

Do not lie or steal.

At the end of chapter 19, the Levitical writers address how to be neighbors, even to foreigners: “When a foreigner resides in your land, you shall not oppress the foreigner. The foreigner who resides among you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the foreigner as yourself, for you were foreigners in the land of Egypt.”

Turns out, scripture is pretty clear about how to treat people and be good neighbors. It isn’t a huge shock. Deep down, under our fear, we know how to be good neighbors.

The huge shock these days is how many Christians would not recognize these instructions from Leviticus and from Jesus, claiming they are some kind of left-wing conspiracy. Elon Musk recently said, “The fundamental weakness of Western civilization is empathy.”

I thought maybe he was alone in making some whackadoodle sort of comment that having compassion for other people was a weakness. And then this week I learned there is a whole movement in evangelical Christianity against empathy. There are bestselling books out with titles like “Toxic Empathy: How Progressives Exploit Christian Compassion.” And “The Sin of Empathy: Compassion and Its Counterfeits.” [3]

Before long, this parable will be banned by corners of the church. It’s a remarkable shift we are observing. We cannot normalize the attempt to erase empathy and compassion from the tenets of Christianity. They are deeply embedded in who we are and in how we are called to live in this world. Don’t let them take it away from us.

Hannah Arendt, who chronicled the Nazi war crimes trials said this: “The death of human empathy is one of the earliest and most tellings signs of a culture about to fall into barbarism.”

Empathy and compassion are deeply embedded in who we are and in how we are called to live in this world. Don’t let anyone tell you it is a weakness or unchristian to care for people.

And even when we believe what the Bible actually says about caring for our neighbors, some days it is harder to live out than others.

Because we are all trying to justify ourselves one way or another.

And this is where I am thankful for grace, the free and un-earned mercy of God that loves and accepts us where we are, but refuses to leave us where it finds us.

The priest and the Levite, walking down the road, are not bad people. They may have been afraid, being on the dangerous Jericho Road, which was just as risky for them as it was for the man, half dead on the side of the road. Maybe they were in a hurry and trying to get off it before dark. They may have been late for a meeting, or on their way to worship.

We are all the priest and Levite some days, seeing people in need of our help, but distracted by many things, or letting our own fears control our actions.

The day before he was murdered, Martin Luther King, Jr preached on this story. And he said "I imagine that the first question the priest and Levite asked was: 'If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?' But by the very nature of his concern, the good Samaritan reversed the question: 'If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?”

We are all on a Jericho Road these days, friends. There are many dangers, toils, and snares, and the road will get even more dangerous for some people, as empathy is banned, as the legal system is weaponized, and protections are eroded and ignored.

And it makes sense that we ask, “If I stop to help this person being harassed on Muni by ICE agents, what will happen to me?”

It makes sense that we ask, “If I speak out against this policy or that injustice, will I end up a target?”

But if we do not stop and help those people, what will happen to them?

What will happen to us if we continue to leave people half dead on the side of life’s roads?

When we see people on the side of a dangerous road and see the half dead part, as Luke described the man, and if we decide that death has already won, we keep on walking.

We might even blame them for being on the road in the first place. ‘Everyone knows the Jericho Road is dangerous business. If you don’t want to be half dead, you should walk on different roads.’

Of course, we say that as if we aren’t all on that same road.

I want us to build a society where we make the Jericho Roads safe for everyone to travel. Yes, it matters that we help the individual people we meet who need assistance. But what if we put up streetlights and increased the patrols on that road?

If empathy is a sin, I want to be guilty of it every single day.

The Samaritan, who would not have been seen as a neighbor by the lawyer or the crowd, managed to see the half of the man that wasn’t dead. The half living part.

As people who serve a resurrected God, one who conquered more than being “half dead”, we should be aware of our tendency to let “half dead” be an excuse to walk on past someone on the side of the road.

We have to be the people who look at the body on the side of the road and see them as half alive. The Samaritan—who worshiped wrong, believed wrong—he managed to live out our faith better than the people who knew the right answers. He saw the man as half alive, and that was enough.

It’s the “glass half full” equivalent for our faith. We are the people called to see the half alive part of everyone we meet, trusting that if resurrection is true for us, that it is also possible for people, half dead on the side of the road. And being a neighbor means we do what we can to help that process.

The Samaritan saw the half alive part of the man, and that was enough for inconvenient compassion to kick in.

I noticed the lawyer, when answering Jesus’ question about which person acted the neighbor, can’t quite bring himself to say the word “Samaritan.” He says, “The one who showed mercy.” It’s not the wrong answer, but it whitewashes things a bit, doesn’t it?

Showing mercy makes it sound like the Samaritan just waved his arm and showed someone mercy at a distance, over there. “Look—theres mercy over yonder! I just showed it to you.”

But acting the neighbor came with a cost. It took time, and his money, that he gave to the innkeeper. It was up close, personal, and an invasion of space. And he likely got blood on his robe, which would have made him unclean. He didn’t just show mercy. He did mercy. Dirty, messy, inconvenient mercy.

In our translation, Jesus says the Samaritan was “moved with pity.” In the Greek, that word in Luke is used as a descriptor of God. The Samaritan is the one who acted as God would act, offering costly compassion and aid to a person half dead on a dangerous road.

Who is our neighbor?

The truth of the matter is everyone in the story should be seen as neighbors. Yes, we are to offer care for the people we find, half alive on the side of the road. And we are to attend to the fact that the Jericho Road is dangerous for everyone and do what we can to change the systems that put everyone in danger, because the priest and the Levite are our neighbors too.

Even that precious lawyer, wanting to test Jesus, is our neighbor, because we know that even the people who have all the answers and want to make sure we know it are God’s beloved children—Jesus loves them too. They are at least half alive.

And sometimes we’re the one in need of the neighbor, in need of the care, the mercy, in need of the person willing to invade our space to save our lives. I confess, I’d much rather be the neighbor than be the person in need.

I also confess that it is in those moments when I’m in need—where I’m not sure whether I’m half dead or half alive—in those moments when someone picks me up, cleans my wounds, puts me on their donkey, and takes me to the ER—that’s when I understand God’s love and the new life of resurrection in new ways.

Because when the world walks on by and determines that you’re half dead, it’s hard to remember the other half, still alive, seeking hope and a second chance.

Friends, wherever you are on the Jericho Road right now, I pray we can be “the glass is half alive” kinds of people, sharing and receiving that promise of hope and resurrection as we need it, journeying toward liberation together.

[3] https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/13/opinion/trump-usaid-evangelicals.html